The Kiwi Adventurer Who Tried to Stop the Titan OceanGate Disaster.

Rob McCallum discusses 11000m sub dives, floating around the Titanic and the deadly deep sea insanity of OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush.

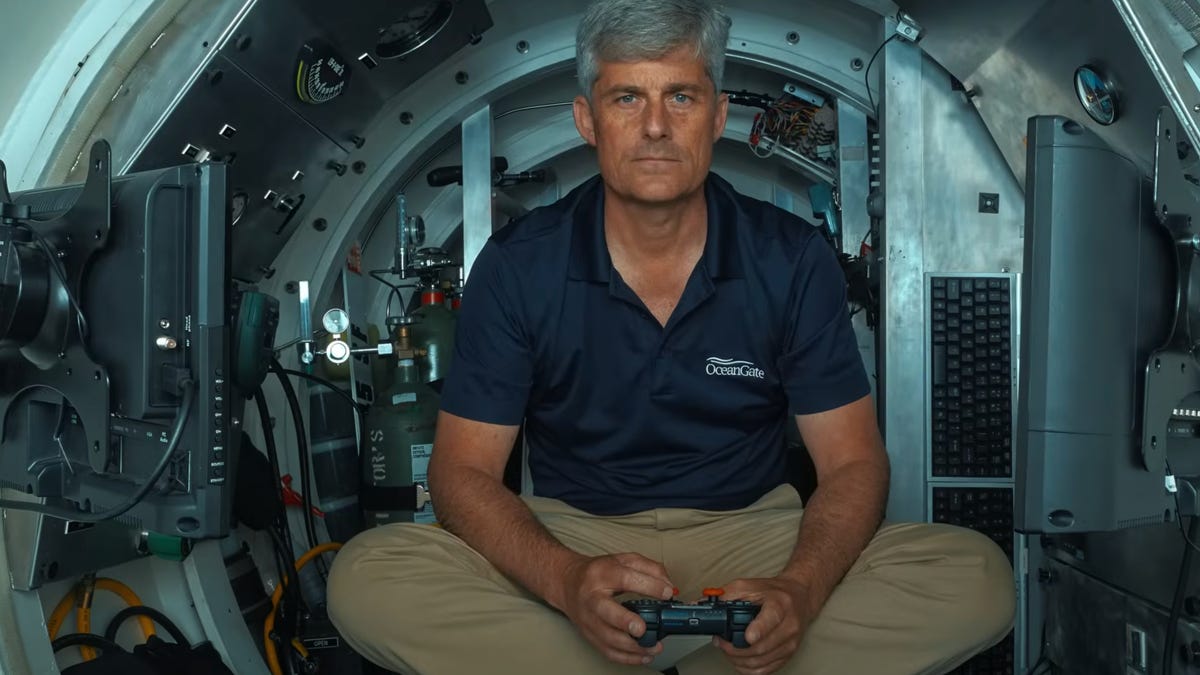

New Zealander Rob McCallum is a pioneer of deep-sea diving. He’s broken the record for the deepest dive in the Mariana Trench—almost 11 000 metres below sea level. He’s worked with the likes of James Cameron and is a key voice in the shocking Netflix documentary Titan: The OceanGate Submersible Disaster. He was the first to warn founder Stockton Rush about the project’s dangers believing the tragic implosion in 2023 was inevitable. The following is an interview Tyler Adams and I conducted with Rob on Friday. We were in our Newstalk ZB studio in central Auckland. He was on his phone, in his truck, on the side of the road in Wayland, Massachusetts.

Rob. For those who may not know your background, what first drew you into deep-sea exploration? Tell us about your career, and how you came to advise OceanGate.

McCallum: I started with 6 000-m vehicles, working on wrecks such as the Titanic and the Bismarck. More recently I’ve worked with full-ocean-depth vehicles that go to almost 11 000 m—the deepest we can go. My involvement with OceanGate was in its early years, when they used classed, certified subs. I left when they decided to head into deep water with an experimental craft.

What’s it like to arrive at Titanic for the first time? That must be quite something.

McCallum: It’s incredible, first because of the size. Unless you’re a dock worker you rarely stand at a ship’s bow and look up at something that massive. At over 880 ft, the Titanic was big. The second impression is grace and beauty—we don’t build liners with that kind of charm anymore. She’s still an incredibly beautiful lady, even in her old age.

How close can you get? Can you float right up on deck?

McCallum: You can, though some areas have debris—lifeboat davits, cables—so you keep a respectful distance. About 15–20 metres is good: your lights illuminate the larger scene and you appreciate the scale and shape from a little way back.

You’ve been deeper than any other human. What’s it like 11 000 metres down? What do you see?

McCallum: Believe it or not, we see life—even at 10 900 m. We also see things never observed before, simply because humans never visit that part of our planet: new life-forms, new bathymetry that helps us understand how Earth was formed.

You’ve orchestrated extraordinary adventures. How does a New Zealander become one of the foremost deep-ocean experts?

McCallum: A happy series of accidents—meeting the right people, being in the right place at the right time. I moved from scuba to shallow subs, then medium-depth subs, then extreme depth. The deep-sub world is small, so reputations form quickly.

Where does the drive come from? Did you have exploration heroes growing up?

McCallum: I follow in the footsteps of Sir Edmund Hillary and Sir Peter Blake. They pursued what they loved with passion, then turned to philanthropy once they’d achieved their goals. That’s the model I try to follow.

You’re obviously not claustrophobic, but do you still feel a healthy fear at extreme depth?

McCallum: Not inside a sub. Everyone feels fear; what matters is how you manage it. People unused to frightening situations freeze like a deer in headlights. Those who face danger often—soldiers, police, firefighters—learn to work through it. The most important part of my job is avoiding risks that create fear. I’m never fearful in a sub because a team of experts has mitigated the risks.

Working with James Cameron and Victor Vescovo, did they share your thirst? Was it fear or excitement for them?

McCallum: Very similar. Jim is an explorer at heart, with filmmaking on the side to fund it. He’s done a great deal to bring ocean exploration to TV screens. Victor is an adventurer; he wanted to reach the deepest point of the world’s ocean, then realised no one had reached the deepest points of the other four oceans, which led to the Five Deeps Expedition.

In the Netflix doc you say there was no way of knowing when Titan would fail, but it was a mathematical certainty that it would fail. What red flags made you walk away?

McCallum: First, Stockton’s unwillingness to listen or consult outside the group. Good leaders solicit counter-views and adjust. If you refuse even to hear them, you’re setting up failure. Second, firing chief pilot David Lockridge for whistle-blowing safety concerns—and then suing him to silence him. That’s a huge red flag.

Stockton Rush seems to have created an almost cult-like following. Was he charismatic? Did he draw you in?

McCallum: Very charming and charismatic, but it was his way or the highway. Tenacious, single-minded, wouldn’t entertain other views. You see through that quickly.

The Titan’s carbon-fibre hull has been called a death trap. In plain language, why does carbon fibre behave so differently under deep-ocean pressure compared with steel or titanium?

McCallum: Steel and titanium are uniform, well-understood metals. Engineers can calculate safe dive depth before a hull is built. With carbon fibre you can’t—its strength depends on fibre quality, resin, humidity, curing temperature, cooling rate. It’s inconsistent, so you can’t predict where or when it will fail.

Watching the documentary, were you alarmed by the evidence—like the audible popping Stockton called “seasoning”?

McCallum: Terrified. None of us in the film had seen all the evidence until the premiere. The popping was the scariest sound I’ve heard underwater. They imploded a half-size model, then another even earlier, then damaged a full hull almost to failure, yet kept diving. I can’t fathom how anyone got in that vehicle twice.

There was a terrible tragedy, but is there some satisfaction for people like Dave Lockridge that the true story is now public?

McCallum: We feel sick, not vindicated. Dave as the inside man and me as the outside man tried hard to stop Stockton. We failed and five people died. Stockton brought it on himself; two others knew the risks; the remaining two were innocents—and that’s what hurts most.

Did you feel you did everything you could to stop this disaster from happening?

McCallum: Formally, we sent information to OSHA and the Coast Guard—state and federal bodies with power to stop it. They didn’t. Informally, I spent three years sabotaging the operation by telling prospective passengers to call me first. We talked about three dozen out of going, including key investors, which may have sped OceanGate’s demise.

How do you deal with people who are so driven but also so cavalier as Stockton Rush?

McCallum: Mavericks aren’t isolated; they’re enabled—by engineers, lawyers, marketers, boards. Anyone who stayed at OceanGate after Lockridge was fired has explaining to do. Those who helped load passengers after “Dive 80,” when the hull was known to be damaged, may face serious consequences.

Your own company operates certified subs with a perfect safety record. What checkpoints do reputable operators follow that OceanGate ignored?

McCallum: It’s called “classing”—certification by an independent society. It starts at the drawing board: design, pressure calculations, material choice. Surveyors witness the forging of the metal, every stage of manufacturing, harbour and sea trials. Finally, a surveyor rides to full depth and signs the certificate at the bottom. You can’t add classing halfway through; it must begin on day one.

What were your first thoughts when you heard the OceanGate disaster had happened?

McCallum: I was on expedition 100 miles north of Papua New Guinea. Around 3 a.m. I got a call: “The sub’s imploded—we heard the signature.” We knew instantly it was fatal. The public “oxygen countdown” puzzled us; the crew died in a blink. I was shocked by how bad things had become inside OceanGate—still can’t understand how the first hull passed sea trials.

Stockton believed it was possible to make money from tourist dives to the Titanic. We know how his venture turned out. Is deep-sea tourism safe if done right?

McCallum: Absolutely. In 50 years tens of millions have ridden certified subs with no incidents. OceanGate operated outside industry rules and paid the price. My most rewarding dive was a tourist sub in Hawaii, watching first-time ocean-goers from Kansas and Oklahoma have their worldview transformed. I hope tens of millions more get that chance—safely.

You sat beside David Lockridge (OceanGate’s former operations director) at the premiere to the Netflix film. In the doco we see how badly he was treated. How he tried to blow the whistle and how he was silenced in court. That seemed to really mess him up. How’s he doing?

McCallum: Much better. He used to swing from survivor’s guilt to rage; now he’s more balanced. The documentary is out; the formal investigation report should be released this month. Federal agencies have been in touch. Justice will be the final chapter.

After decades underwater, are you still passionate about the deep? Has the accident tainted your feelings toward the industry?

McCallum: We run an expedition company with more than 1 800 safe, successful missions. I don’t call myself an explorer because people expect a pith helmet and a tiger gun, but full-time exploration is what we do—mostly identifying and mitigating risks before leaving home. A world record only counts if everyone returns alive. The ocean covers 71 % of Earth, and it holds answers to future human challenges. We’re not stopping.

Rob, thank you so much. You’re a great New Zealander. It’s been an honour to talk with you.

McCallum: Thanks for having me.

Tune into Matt Heath and Tyler Adams Afternoons weekdays 12-4 on Newstalk ZB